The cocotb project is proud to announce the immediate release of its new version 1.6.0. cocotb is a COroutine based COsimulation TestBench environment for verifying VHDL/Verilog RTL using Python.

Cocotb can be installed and updated from PyPi through pip:

python3 -m pip install --upgrade cocotb

For full installation instructions refer to the documentation at https://docs.cocotb.org/en/v1.6.0/install.html.

This release concludes a seven month development period. Instead of going directly to cocotb 2.0, we threw in another backwards-compatible release in the 1.x release series with a number of exciting new features, and deprecations for functionality we will change in cocotb 2.0.

All users of cocotb are strongly encouraged to look through the deprecations when running their tests and future-proof their testbenches as time permits!

Read on for some of the highlights in this release.

New ways to schedule coroutines

Coroutines are at the heart of cocotb -- it's even in our name!

Since early on coroutines could be scheduled to run concurrently with cocotb.fork().

That still works -- but now there's a better way as well, and we encourage you to update your code.

In cocotb 1.6, we're introducing a new way of scheduling coroutines using cocotb.start_soon().

Additionally, we're introducing two less commonly used functions, await cocotb.start(), and cocotb.create_task().

Before we go into the details, the quick porting advice is:

In most cases, you can simply replace cocotb.fork() with cocotb.start_soon().

Coroutine basics

To understand the differences between the various ways of scheduling a coroutine we need to first recap the basics behind them.

A coroutine function, in cocotb, is a Python function declared with async def.

Coroutines can be executed in parallel -- in theory.

In practice, there's only one coroutine running at any given time.

So we need to choose which one gets to execute.

Two potential solutions come to mind: we could, option one, introduce a "moderator" which allows, for example, a first task to execute for a bit, and then lets a second one execute, and so on. Or, option two, we could teach tasks (at moments they find suitable) to ask around if other tasks would like to do some work as well, and pass over control to them. Coroutines (not only in cocotb) implement the second concept: be nice to each other, and give up control when no work is left for the moment.

In cocotb, you use the await statement to yield control, that is, give up control and indicate that another coroutine may now execute.

The execution resumes in the line after the await statement once the event specified after await has happened.

Schedule a coroutine using cocotb.start_soon()

That's a lot of introduction: let's get back to cocotb.fork(), cocotb.start_soon(), and await cocotb.start().

What's common to all these three functions is that they schedule a coroutine, which only means: these functions let cocotb know that a coroutine exists, and that it would like to run at some point.

The cocotb scheduler will then take care of the rest.

What distinguishes the three functions is what they do in addition to scheduling the given coroutine.

For cocotb.start_soon() the answer is easy: nothing.

A coroutine is only introduced to the scheduler, which will hand over control to it as soon as another coroutine gives up control.

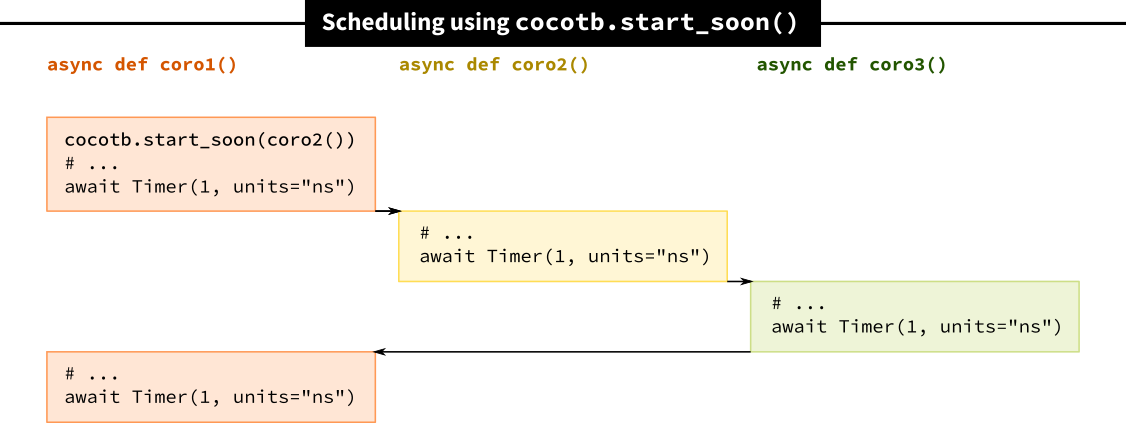

Let's have a look at the figure above to understand how the scheduling could look.

Assume coro3() has been scheduled earlier and is ready to execute.

coro2() is scheduled by coro1().

Since we're using cocotb.start_soon(), coro2() is only scheduled, but not executed until coro1() yields control using an await statement.

At this point, also coro3() will execute, and ultimately, control will return to coro1().

Schedule and run coroutines using await cocotb.start()

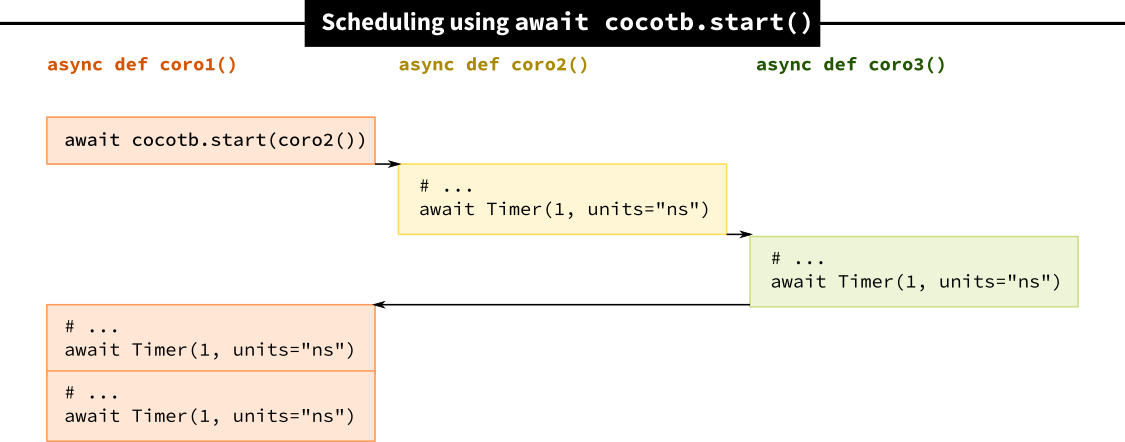

Things looks slightly different when using await cocotb.start(): cocotb.start() schedules a coroutine, and immediately yields control to let any other coroutine execute.

Since cocotb.start() yields control, it needs to be used in conjunction with await.

As shown in the figure, once coro1() yields control, both coro2() and coro3() run.

Only then control returns to coro1().

You can think of await cocotb.start() as a combination of cocotb.start_soon() and await NullTrigger(), which is a trigger that immediately fires.

In almost all cases you won't need the immediate trigger that await cocotb.start() provides, and you can use cocotb.start_soon() instead.

The old way: cocotb.fork()

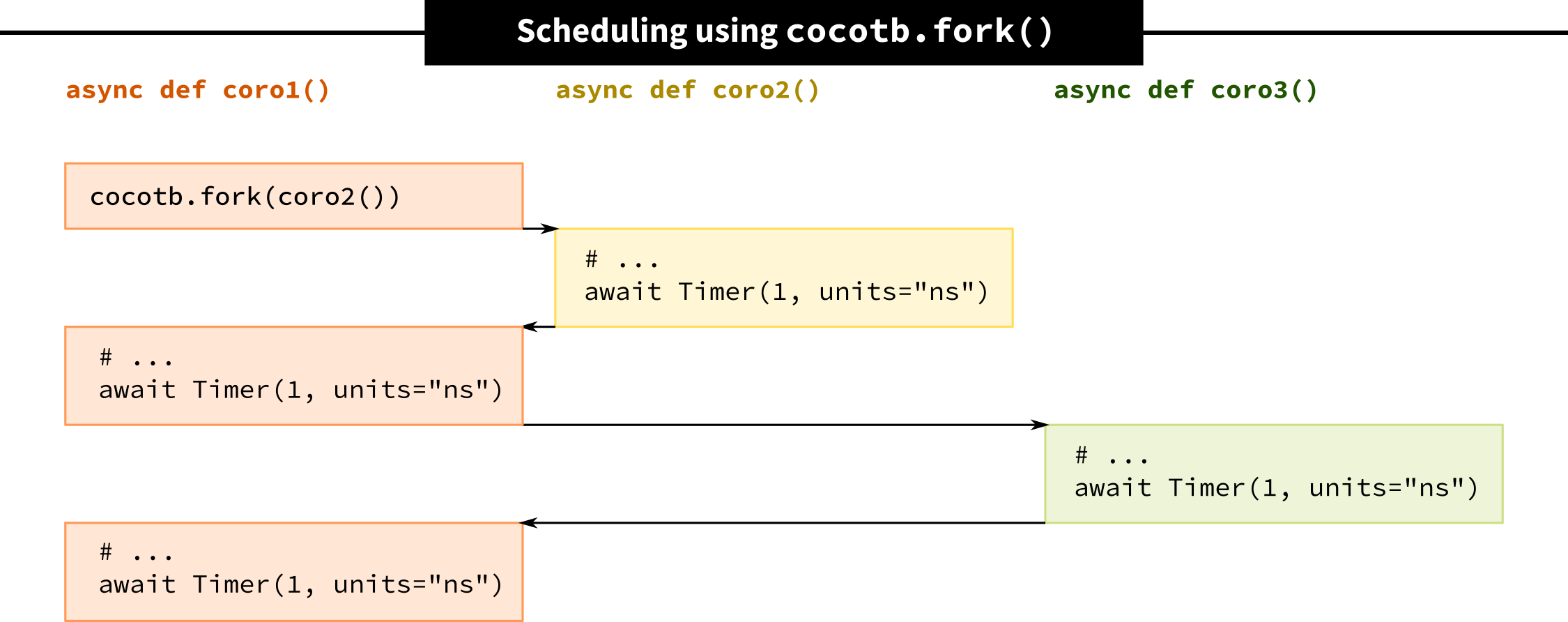

Finally, there's the third and "old" way of scheduling a coroutine: cocotb.fork().

cocotb.fork() schedules the coroutine, executes only this coroutine until the next await statement, and then returns to the caller.

In the figure above, coro1() forks off coro2(), which then executes until the next await statement.

Then execution returns to coro1() and it executes until it yields control in an await statement.

Only then can all other coroutines, e.g. coro3() do their work.

We deprecated cocotb.fork() because it has slightly odd behavior (by today's standards, of course):

cocotb.fork()gives up control, but isn't a async function which needs anawaitin front of it.cocotb.fork()yields control "only a bit" to let exactly one other coroutine execute, but in a way which is rather unique.- And finally there are a several other corner cases in error handling which are very hard or impossible to get right with

cocotb.fork(), and which many users have painfully experienced over the years.

cocotb.fork() is deprecated, but it will remain available in cocotb 1.x.

We encourage you to migrate your testbenches to the new scheduling routines, most likely by simply replacing cocotb.fork() with cocotb.start_soon().

Have a look at PR #2713 for how we did the conversion in cocotb itself.

Further reading

If you'd like to know more about coroutines and scheduling in cocotb have a look at the Coroutines and Tasks section in the documentation (which also explains the cocotb.create_task() function, which we skipped here).

They are your type: HDL datatypes

Datatypes are behind every line of code in your editor.

When you write logic [3:0] my_signal in SystemVerilog datatypes are clearly visible.

But datatypes are there even if you don't explicitly write them down, as in my_signal <= -2 in cocotb.

Right now, cocotb is fairly relaxed about HDL datatypes, and freely converts between them as needed mostly through its BinaryValue class (which is behind the my_signal assignment seen before).

However, being relaxed isn't always helpful, as some cocotb users have found out: conversions can go wrong, and expressiveness can be be lost.

Starting with cocotb 1.6, we're introducing datatypes which model common HDL data types: Logic for four-state logic values, Bit for two-state logic, Array and LogicArray for HDL-style arrays or vectors.

All these new types have been carefully designed to feel natural for both VHDL and SystemVerilog programmers, and to provide type safety and useful typecasts.

As of now these datatypes can be used in custom testbench code. Going forward, we plan to bake these types more deeply into cocotb, and make signal handles return them.

Assigning values to signals using <= is deprecated

One of the unique, but also slightly obscure, features of cocotb is on its way out:

Setting values on handles using the my_signal <= newval syntax is now deprecated.

Please use my_signal.value = newval instead.

We didn't take this decision lightly (it's more typing, after all!), but there are good reasons for it.

- First of all, the syntax doesn't always work (and there's no way of fixing it).

Quiz: What do you think

a <= b if c else ddoes? (Answer) - It's not obvious what

<=does for someone who knows Python. We got asked many times, and every presentation introducing cocotb has to explain it. It's even hard to google for it! - Finally,

<=provides more than one way of doing things, which is bad for teaching and learning cocotb.

So if you have a spare moment, open the search-replace dialog of your favorite editor, and get rid of a couple <= assignments!

GPI +- cocotb

Cocotb does a lot of hard work to provide a common interface between simulators and your Python testbench. Within cocotb, this abstraction layer is called GPI. So how about a crazy idea: you want to write your own cocotb-like framework in Python, but don't want to do the hard work of creating an abstracted interface to all those simulators out there? You can do that now by providing a custom entry point, which is a Python module which implements a couple functions. This feature is experimental and isn't guaranteed to stay this way going forward, but that shouldn't discourage you from giving it a try (but don't get too excited just yet and build your whole infrastructure around it!).

Build system improvements

A staple of cocotb releases are improvements to its testbench build system. This time around, key improvements are:

- ModelSim, Questa, and Xcelium now support compilation into a named VHDL library lib using

VHDL_SOURCES_<lib>. - A new

SIM_CMD_PREFIXMakefile variable can be used to prefix simulation commands. This feature is helpful to run commands in GDB, add a library usingLD_PRELOAD, or run commands through a job scheduler.

Closing notes

A much more detailed description of all changes in this first 1.6 release can be found in the release notes.

Cocotb is a community project under the umbrella of the FOSSi Foundation. Thanks to all sponsors of the FOSSi Foundation the cocotb project can make use of a continuous integration system which runs proprietary simulators in a compliant way.

We are very thankful to Aldec for providing a license for Riviera-PRO, and to Siemens EDA for providing a license for Questa, which enables us to continuously test cocotb against these simulators to ensure they continue to be well integrated.

Please reach out to Philipp at philipp@fossi-foundation.org if you or your company want to support cocotb, either financially to help pay for costs such as running our continuous integration setup, or with in-kind donations, such as simulator licenses.

To close this rather long release announcement, here are some statistics:

326 files changed, 9694 insertions(+), 14361 deletions(-)

153 commits

15 code contributors

These numbers are impressive and showcase the power of the free and open source collaboration model. To be able to sustain this amount of change and the high-quality review process behind it we are happy to have an active group of maintainers caring for cocotb and its users. Thank you, and thanks to the whole cocotb community for coming together to create this unique piece of software.

And now, go and enjoy the best release of cocotb so far!

If you have questions or issues with this release head over to the issue tracker.